“This is a time for action,” writes Peter Drucker in Knowledge Society. And “active” seems the right word to define the life of Hazel Henderson who, from starting the civic movement Citizens for Clean Air to tackle air pollution in New York City, developed into a futurist, sustainable development consultant and economic writer.

In the following interview, I have talked with her about the role of education, sustainability and the meaning of qualitative growth.

Can you please summarise your background and your experience as an activist, writer and consultant?

I am self-educated. I went to a very good school in the United Kingdom that gave me solid reading, writing and English basics. However, as society was changing rapidly it seemed to me that a lot of what I wanted to learn wasn’t yet being taught at university, so in my case not going to college turned out to be a big plus.

My experience as an activist began in 1964, while I was living in New York, when as a housewife and mother concerned about her child’s health, I started Citizens for Clean Air.

As a newly naturalised US citizen it was thrilling to learn so much from the activities of being involved in a community organization, which led me to read a huge amount of information about pollution and where it was coming from, corporations, theory about corporations, and all that. As time went by, our grassroots movement grew to 40,000 strong, with block captains in every New York borough. It made a lot of connections, so for example we went to annual meetings of General Motors to try to appoint citizens in the board of directors.

I was also able to speak to the Mayor of New York, but, when I asked him about pollution issues, his reply was that there was no such thing as smog, which he dismissed as mist coming from the sea.

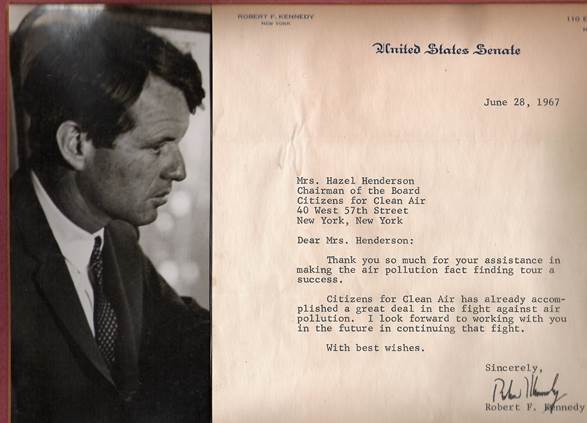

At that point we invited our newly elected Senator Robert Kennedy for a helicopter ride around the city, who understood the seriousness of the problem, which was generated by chimneys, power plants and factories.

When my Citizens for Clean Air experience came to an end, I wrote a 10,000 word article about the responsibility of businesses which I sent to the Harvard Business Review. After a couple of weeks they sent me a letter to make sure I really was the person who wrote it, as normally if you have an article published in the Harvard Business Review everyone assumes you have a PhD!

To my amazement, they went on to publish my article under the title Should Business Tackle Society’s Problems?, which catapulted me onto a global scene. As a consequence, I started teaching Business Ethics courses and, realising how vast the subject was, I pulled it all together in a book, Creating Alternative Futures.

It is true that all the things you do set you up for your whole life.

You have battled against the view that sees the GDP as the indicator of a country’s wealth and prosperity. Could you please explain why we should not use it as the only element to rely on to assess a nation’s standard of living?

When the Mayor of NYC told us that there was no pollution, we realised that the GDP kept adding up all the bads along with the goods and so one of our main goals was to correct the GDP and make sure that the pollution and the other bads would be subtracted from the goods in order to come up with a net figure which could be more realistic. Senator Robert Kennedy helped us a lot when gave a wonderful speech at University of Kansas in 1968 on all the things that are wrong with GDP.

In a way, it became a crusade for me, so I spoke at many at civic organizations, then I went to the first Earth Summit as a journalist in Stockholm – in 1972 – and spoke and wrote about it, but nobody listened to me.

However, after the huge impact made in 1992 by the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, in 2007 I helped to organise a conference in front of a packed EU Parliament called Beyond GDP. At last, the topic was on the political agenda.

I think that with the Sustainable Development Goals approved in 2015 in New York last summer we have finally made the GDP obsolete.

Some might think that the GDP and other statistics are just abstract data that do not have an impact on daily life. However, numbers can give a wrong perception of reality, causing people and entire nations to suffer. On the contrary, if interpreted correctly, figures can help to boost a country’s prosperity. What is your experience about this?

In 2003 I assisted in organising the first international conference on New Indicators of Sustainability and Quality of Life in Curitiba, Brazil, because we had all these figures such as health poverty gap and environment statistics and they all need to be crammed in and given as much weight as the economic statistics. That did change the policies in Brazil and I am going to explain why, as in my article “Statisticians of the World Unite,” Inter Press Service, 2003.

At that time, everyone said Brazil had a huge debt-to-GDP ratio, but the country was investing in infrastructure and sanitation, and all that money invested in improving the country was counted as debt while it was actually very valuable asset they were creating.

So the Finance Minister of Lula went to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) with our report and asked why they were overestimating their debt and not accounting for all the assets they were creating.

It was then that the IMF changed the way they looked at the Brazilian economy and cut Brazil’s debt in half with one stroke of the pen. That’s how powerful good statistics are.